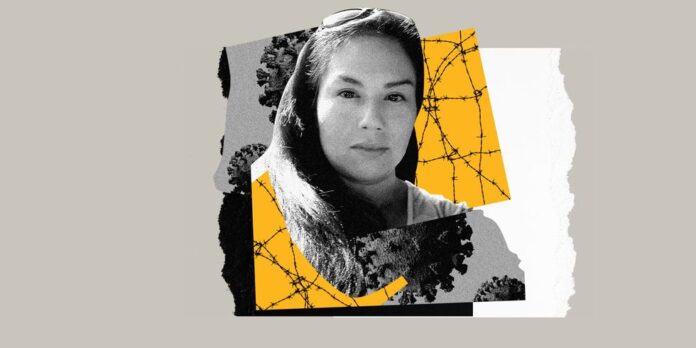

When she was seven months pregnant, Andrea High Bear called her grandmother from a South Dakota jail with bad news: She had been cleared to fly. That meant High Bear, a 30-year-old sentenced to over two years on a federal drug charge, would be transferred to a prison far from her home in South Dakota, where her five children and family lived. It was late March, and coronavirus was starting to rage. “We were both aware of what was going on with the virus,” says her grandmother, Clara LeBeau. “She’s afraid, not knowing what was gonna happen.”

Two weeks after being transferred to a Texas prison, High Bear had her baby. But she never met her little girl. By then, High Bear was on a ventilator, diagnosed with coronavirus. On April 28, she died, making her the first female federal prisoner to die of coronavirus.

With tight living spaces, little fresh air, and limited access to hygiene, prisons and jails are ripe for spreading coronavirus. From California to Ohio to Florida, cases are soaring in state and federal prisons and jails, amplified by overcrowding, lack of cleaning supplies, and subpar medical care. More than 500 prisoners have died from coronavirus, and almost 44,000 have had the virus, according to The Marshall Project.

Federal prisoners who feel endangered by coronavirus can ask the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) to allow them to finish their sentence at home. If the request is denied, they can ask a federal judge for “compassionate release.” The BOP says it considers prisoners’ age, health, and prison conduct, among other factors, in approving home confinement.

"She never should’ve been in custody in the first place at that stage in her pregnancy."

Around the same time as High Bear was languishing in prison, other high-profile and well-connected federal inmates like Paul Manafort and Michael Cohen were being released to home confinement due to the coronavirus. But they were the exception: Overall, only about 4,200 prisoners, or 2.6 percent of the federal prison population, have been released to home confinement due to virus concerns since late March. Others, who can’t afford lawyers or who have trouble navigating the confusing systems to be considered for release, are left vulnerable in dangerous institutions. “There cannot be two justice systems,” Senator Amy Klobuchar tweeted recently, comparing High Bear’s treatment to the release of Manafort and Cohen.

“Inmates’ safety is not a priority,” says Deirdre von Dornum, attorney-in-charge of the Federal Defenders of New York, which is suing New York City federal jails to improve coronavirus precautions. “Each of the deaths in custody seemed to me likely to be preventable.” Given High Bear’s pregnancy and nonviolent history, Von Dornum says her sentencing judge could have let her serve her sentence at home. “Her case seemed particularly upsetting,” she says. “She never should’ve been in custody in the first place at that stage in her pregnancy.”

Growing up in South Dakota, High Bear was the oldest of eight kids. She played basketball and softball, and spent summers on the Cheyenne River Sioux reservation in Eagle Butte, where her grandmother, LeBeau, lives, attending Bible camp and hanging out with cousins.

High Bear married at age 19 and had children young, withdrawing from community college to be a full-time mom. Her oldest child, now 10, helped her make pies, dinner rolls, and cinnamon buns so delicious that she sold trays of them on the reservation.

Sadness lingered in the background, though. In 2014, her sister-in-law, Sarah Lee Circle Bear, died in a South Dakota jail. She’d been brought in on a bond violation after a traffic stop. State officials said she died of a methamphetamine overdose and had smuggled drugs into the jail. Her family challenges this, questioning how she got meth in jail when she was in custody for a day and a half, and saying they were told by another inmate that she had been repeatedly asking for help when she died.

Both Andrea and her sister-in-law having encounters with law enforcement underscores a grim reality for Native women in South Dakota. While Native American women make up only 9 percent of the state’s population, they are almost half of its female inmates, according to Prison Policy Initiative figures.

In March 2019, High Bear was arrested on federal drug charges, for selling about $850 worth of meth to an undercover informant. After her arrest, an acquaintance, Robin Hamm, stayed with High Bear and her then-husband (who she divorced not long before her death) on the reservation. “She sat down with me and she said, you know, I’ve done wrong, and I want to be a good mom, and I want to be out here [with her family],” Hamm says. Adding that Andi, as friends called her, was “just so gracious in what I think would be one of the hardest moments of your life.”

In October 2019, High Bear pled guilty to one drug-related count and was sentenced to more than two years in prison. She had only been in jail for a little over five months when LeBeau received the unnerving phone call from her saying she’d be transferred. High Bear’s pregnancy was high risk, because of five previous C-sections, and LeBeau and High Bear both hoped she’d be able to deliver the baby in South Dakota.

But the next time High Bear called, a few days later, it was from a prison in Fort Worth called the Federal Medical Center Carswell. She’d been screened upon arrival, according to a Bureau of Prisons spokesman, and “did not report” coronavirus symptoms. Still, she was quarantined as a precaution.

"They made mistakes. It does not mean they signed up for a death sentence."

Retta Sundblad, another Carswell inmate, was quarantined at about the same time as High Bear. She describes the setup as “being in an old motel”: the room had decades-old carpeting, a hole in the ceiling, and no bathroom sink. Women could only leave their rooms for 20 minutes each day, she says.

Carswell seemed to be playing catch-up with coronavirus, according to Sundblad. In late March, before she was quarantined, Sundblad had a routine hospital check-up. Going to the appointment, outside of prison, Sundblad was startled to see empty roads and everyone in masks. Upon returning to prison, “I’m thinking, well, surely they’re gonna put me in isolation because I’ve been out and potentially exposed,” she says. “Nope: I went right back to my room and was with everybody.”

At other jails and prisons, preparation was similarly scattershot. At the Manhattan federal jail, as of mid-March, there was no testing protocol, plan for where to place symptomatic inmates, or screening of inmates, its warden testified in May. In Louisiana, prisoners described making masks from their clothing as cellmates developed fevers. In Illinois, jail staff said there wasn’t adequate access to hand sanitizer.

Ashunda Harris, whose sister is also incarcerated at Carswell and whose brother is in prison in Illinois, has been calling their prisons for weeks to get them screened for home release. “I’m getting voicemail, I’m getting leave-a-messages, I’m getting no returned phone calls, nothing,” she says.

Her sister, Sandra Shoulders, is 55, has diabetes, and wrote to me from Carswell, to say she’s been re-washing the same face mask for a month. “I wish I could afford a private attorney,” Shoulders wrote.

On March 31, High Bear told LeBeau she was in the hospital with pneumonia. When the government flew her from South Dakota, LeBeau says, “It was so cold and she didn’t have a jacket or anything, and that’s where she must have caught a cold and it turned to pneumonia.” The day High Bear left South Dakota, the temperature hit a low of 9 degrees. What LeBeau didn’t yet know, and wouldn’t learn for several days, is that High Bear had tested positive for coronavirus, according to a Bureau of Prisons spokesman. “She told me to tell her kids that she loved them, and loved me, and then we prayed together, and that was the last time I talked to her,” LeBeau says.

Lynzey Donahue, a spokeswoman for the U.S. Marshals Service, which moves federal prisoners, says that once the marshals got assurance from High Bear’s health-care provider that she could fly, it took precautions like same-day “nonstop movement.” Prisoners travel in prison-issued clothing and “care is taken to reduce exposure” from bad weather, the spokeswoman says, adding that the Marshals Service does not move prisoners symptomatic or positive for COVID and cleans its vehicles daily.

On April 1, High Bear gave birth while on a ventilator. “I said, ‘Does she know about the baby?’, and they said, ‘No,’” LeBeau says. High Bear had picked out a name: Elyciah Elizabeth Ann, the middle names matching those of her two sisters who had died. (In 2017, her sister Megan Elizabeth died in a snowstorm, and later that year, her sister Ronni Ann died of unknown causes.)

In mid-April, LeBeau brought Elyciah home. Self-quarantining with the baby, LeBeau held Elyciah to the window so her five siblings, who live next door, could meet their sister.

On April 28, the hospital called to say High Bear had died.

A B.O.P. spokesman, Justin Long, says every eligible pregnant inmate has either been released or sent to home confinement. In High Bear’s case the sentencing judge “felt that placement of Ms. Circle Bear in a federal medical center was in her best interest as FMC Carswell would have been able to provide the court recommended drug treatment and appropriate medical care for her pregnancy,” the spokesman says. Because “in this particular instance, the inmate was quarantined and fell ill soon after,” her medical care there “precluded her consideration for home confinement,” which was unlikely to be granted anyway given that she’d just arrived at Carswell.

LeBeau says she wishes she had fought for High Bear to stay in South Dakota or to get home confinement. “We just figured that’s the way it is, and we accepted it,” she says.

Advocating, though, doesn’t always bring results in the prison system, says Harris, the woman working to get her siblings home release. “They made mistakes,” she says of her imprisoned siblings. “It does not mean they signed up for a death sentence.”

In early May, High Bear’s family, wearing masks, attended her Eagle Butte funeral. A small boy wiped tears away. A man rested his head against her casket. At the end, pallbearers took High Bear’s casket outside the funeral home, through heavy rain and wind, and raised it into a hearse, where it would continue on to be buried in the green and gold South Dakota earth.

Stephanie Clifford Stephanie Clifford is an award-winning journalist writing about criminal justice and business, and author of the bestselling novel Everybody Rise. This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io This commenting section is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page. You may be able to find more information on their web site.